Creating PostgreSQL locks with Docker

I used to try and understand how databases work by just reading the documentation, but one day I realized that everything in the docs can be recreated with relatively little effort. Recently I was reading PostgreSQL documentation on how database locks work, and I realized I wasn’t fully comprehending the content of the documentation. So I figured I would try it out with a bare-bones database.

Step 1

Create an empty database with PostgreSQL.

This can be done really easily using docker and a PostgreSQL docker container. If you do not have docker running you can find out how to install it here: https://docs.docker.com/

docker run --name postgres-lock-test -e POSTGRES_PASSWORD=s -d postgres

That’s it! You now have PostgreSQL running locally.

Step 2

Create a table and insert some data.

To do this we can use PostgreSQL’s command line tool psql and we use the CREATE TABLE command and INSERT command.

docker exec -it postgres-lock-test psql -U postgres

postgres=# CREATE TABLE dawgs (

id serial PRIMARY KEY,

name varchar(40)

);

postgres=# INSERT INTO dawgs (name)

SELECT 'Dawg number: ' || number

FROM generate_series(1,10000) AS number;

Boom! We now have a database with one table and a bunch of data in that table. Here is a quick look at the first 10 rows of the data.

postgres=# SELECT * FROM dawgs LIMIT 10;

id | name

----+-----------------

1 | Dawg number: 1

2 | Dawg number: 2

3 | Dawg number: 3

4 | Dawg number: 4

5 | Dawg number: 5

6 | Dawg number: 6

7 | Dawg number: 7

8 | Dawg number: 8

9 | Dawg number: 9

10 | Dawg number: 10

(10 rows)

Step 3

Create some locks.

To create some locks in that database that interact with each other we can use two psql instances running at once, and with the BEGIN command we can start up transactions on both those two psqls so that the locks won’t free up until we use the END command.

docker exec -it postgres-lock-test psql -U postgres

postgres=# Begin;

BEGIN

postgres=# UPDATE dawgs SET name = 'Ben Dawg' WHERE id = 123;

UPDATE 1

postgres=#

# in another psql

docker exec -it postgres-lock-test psql -U postgres

postgres=# Begin;

BEGIN

postgres=# UPDATE dawgs SET name = 'Ben bro' WHERE id = 123;

# Notice your prompt is stuck waiting for the above command to run.

Shazam! We created two transactions. The first transaction is locking one record that the second transaction is also attempting to update.

Step 4

Make sense of the PostgreSQL internal stats tables.

We are able to find these locks in the different pg stats tables. The PostgreSQL internal tables can be helpful to track down lock related issues. To try this out we can keep the two psql instances above open and create a new psql that looks at the pg_stat_activity table.

docker exec -it postgres-lock-test psql -U postgres

postgres=# SELECT pid, state, query

FROM pg_stat_activity

WHERE application_name = 'psql' AND wait_event IS NOT NULL;

pid | state | query

-----+---------------------+----------------------------------------------------

91 | idle in transaction | UPDATE dawgs SET name = 'Ben Dawg' WHERE id = 123;

107 | active | UPDATE dawgs SET name = 'Ben bro' WHERE id = 123;

(2 rows)

This is showing us what processes are querying the database. The state column is important because it tells us what the different processes are doing. When pg_stat_activity.state is 'idle in transaction' we know that we have an open transaction that is holding a lock but isn’t doing anything else in the database. In our above example the first transaction is left open after locking a row in the dawgs table and psql is waiting for more commands.

Our second psql cannot edit the same row as long as the first transaction is held open, and the first psql is considered idle because there is no active query being run on it. In a production environment this can be a symptom of a large issue, possibly meaning that our application is locking the data but then gets sidetracked with something else before closing the transaction. More information about the different data in this table can be found here: https://www.postgresql.org/docs/10/static/monitoring-stats.html#PG-STAT-ACTIVITY-VIEW.

After having looked at the activity in the database we are able to review the locks themselves using the pg_locks table. This query uses our above search to find the process id (PID) of our locking transactions, then we use that PID to query the pg_locks table.

postgres=# SELECT mode, pid, relation

FROM pg_locks

WHERE pid IN (SELECT pid

FROM pg_stat_activity

WHERE application_name = 'psql'

AND wait_event IS NOT NULL);

mode | pid | relation

------------------+-----+----------

RowExclusiveLock | 107 | 16390

RowExclusiveLock | 107 | 16386

ExclusiveLock | 107 |

RowExclusiveLock | 91 | 16390

RowExclusiveLock | 91 | 16386

ExclusiveLock | 91 |

ExclusiveLock | 107 |

ExclusiveLock | 107 | 16386

ShareLock | 107 |

ExclusiveLock | 91 |

(10 rows)

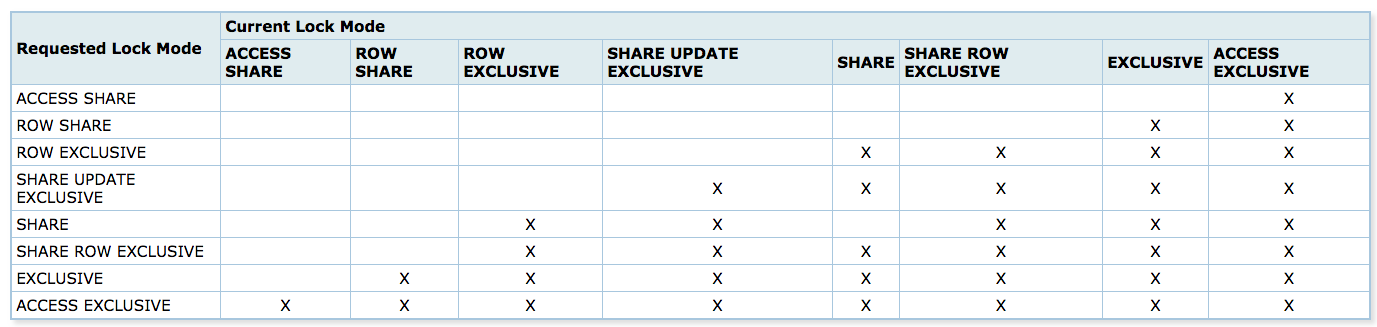

We are able to use the pg_locks.mode column to tell how serious of a lock we are dealing with, and using the PostgreSQL’s documentation we can tell what activity that sort of lock will prevent. We can also look up what object is being locked by using pg_locks.relation and the pg_class.oid.

postgres=# SELECT relname

FROM pg_class

WHERE oid IN (SELECT relation

FROM pg_locks

WHERE pid IN (SELECT pid

FROM pg_stat_activity

WHERE application_name = 'psql'

AND wait_event IS NOT NULL));

relname

------------

dawgs

dawgs_pkey

(2 rows)

We can put all of these ideas together to make a query that will show us all of the different types of locks that currently exist on our database.

postgres=# SELECT locks.pid,

Array_agg(DISTINCT( MODE )) AS MODE,

Array_agg(DISTINCT( relname )) AS relname,

Max(query)

FROM pg_catalog.pg_locks locks

join pg_catalog.pg_stat_activity activity

ON locks.pid = activity.pid

join pg_class class

ON class.oid = locks.relation

GROUP BY locks.pid;

-[ RECORD 1 ]-----------------------------------------------

pid | 91

mode | {RowExclusiveLock}

relname | {dawgs,dawgs_pkey}

max | UPDATE dawgs SET name = 'Ben Dawg' WHERE id = 123;

-[ RECORD 2 ]-----------------------------------------------

pid | 107

mode | {ExclusiveLock,RowExclusiveLock}

relname | {dawgs,dawgs_pkey}

max | UPDATE dawgs SET name = 'Ben bro' WHERE id = 123;

Step 5

Have some fun, and play around a little.

I recommend trying to create the different types of locks listed in the PostgreSQL documentation.

* Screenshot taken from PostgreSQL documentation.

* Screenshot taken from PostgreSQL documentation.

It can also be helpful to run select statements from the different transactions to see what data each transaction recognizes as having been updated. You may also want to come up with your own query to identify troublesome locks in your database by using the pg internal tables. This wiki page https://wiki.postgresql.org/wiki/Lock_Monitoring is also helpful when trying to find locks, but the queries can be heavy handed so understanding the basics can help you modify them to suit your needs.